I am a sucker for a good book cover. So, while I hadn’t registered the hype over A. J. Finn’s debut novel, The Woman in the Window, the book had caught my eye in a bookshop. And as I am also a fan of Jimmy Stewart’s Alfred Hitchcock movies, I was intrigued by its homage to the 1954 classic, Rear Window.

What spurred me to buy the book wasn’t the cover or my Rear Window curiosity, but the furore caused by the article in The New Yorker (11 February 2018) exposing the deceptions of the man behind The Woman in the Window. And a subsequent Better Reading podcast (8 February 2019) interview with the man, who writes as A. J. Finn, Dan Mallory.

Bald-Faced Deceptions

A pseudonym is not uncommon among writers; Wikipedia lists a page of notable nom de plumes (A. J. Finn wasn’t on the list, so I added him). And in Mallory’s case, as a well-known editor in the publishing industry, where a debut flop could be embarrassing and career-ending, pitching his novel as A. J. Finn proved a wise commercial move.

However, the litany of bald-faced deceptions discredited in The New Yorker article by Ian Parker is breathtaking and suggests a flawed character worthy of inclusion in a psychological thriller. Some of Mallory’s more fanciful claims about his health and family, qualifications and career include:

- He had recovered from several bouts of cancer, including an “inoperable brain tumour”.

- His mother had died of cancer — Mallory’s mother battled breast cancer in his teenage years but survived.

- Various stories about his (healthy) brother being “mentally disadvantaged”, having cystic fibrosis, dying while being nursed by Mallory, and committing suicide.

- A doctorate from Oxford University — Mallory studied at Oxford but did not complete his degree.

- He was an editor at Ballantine Books (US imprint of Random House) — Mallory had been an assistant to the editorial director.

- J. K. Rowling’s The Cuckoo’s Calling was published by Little, Brown Books UK on his recommendation — The New Yorker asserts Mallory might have read the manuscript, but it was not published on his recommendation.

Before the article’s publication, Mallory provided a statement to The New Yorker, apologising for having “stated, implied, or allowed others to believe that I was afflicted with a physical malady” and “taken advantage of anyone’s goodwill”.

He blamed the deceptions on years of “psychological struggles”. Rather than reveal his mental illness earlier, Mallory claimed, “Dissembling [had] seemed the easier path.”

Better Reading Podcast

Mallory acknowledged his mental health issues in the Better Reading podcast interview with Caroline Overington. At twenty-one, he was diagnosed with severe clinical depression. He’d resorted to “every treatment imaginable”, from medication to meditation, hypnotherapy and electroconvulsive therapy. However, none had proved “lastingly fruitful”.

On his thirty-sixth birthday three years ago, Mallory saw another psychiatrist who determined he had been misdiagnosed and instead had a form of bipolar disorder. “Within about six weeks” on his new regime of medication, he felt “altogether restored, totally transformed”.

Having worked through mental health issues for over fifteen years and written a best-selling book where the protagonist has agoraphobia, Mallory has taken it upon himself to speak out on mental health. As he said in the podcast, “It is a subject that is under-discussed. It is little understood and much stigmatised.”

I couldn’t listen to the Better Reading podcast without thinking of The New Yorker article. Mallory sounded charming and self-assured on the podcast, yet claimed to be shy. Was he overcompensating for his shyness? Despite being “restored”, was that why he repeated the deceptions about his CV that The New Yorker had exposed?

I’d posted a question to my Facebook page when The New Yorker article broke: Is it okay for a fiction writer to make up a disease and details about his CV in his author bio?

Literary Scandals and Hoaxes

Better Reading explored the question in greater depth on their A. J. Finn follow-up podcast on Literary Scandals and Hoaxes (19 February 2019), where Cheryl Akle and Caroline Overington discussed the Mallory scandal (and other more infamous and close to home literary hoaxes).

At the end of the podcast, Overington asserted, “[Mallory] didn’t really lie to us at Better Reading.” He had not said his mum was dead or that he had cancer, or that his brother had suicided. She admitted feeling “a bit bruised” about the interview and the Oxford doctorate lie, but she still praised Mallory’s book as a “great read”.

Akle, however, commented, “[The scandal] has certainly devalued that book for me.”

A Sucker

Shortly after The New Yorker article and the first Better Reading podcast, I was in a supermarket check-out queue when I spotted the distinctive book cover of The Woman in the Window on an impulse-purchase shelf. I thought of the Mallory scandal, I thought of the fantasy world I inhabit when writing and the half-truths I’ve told in my life, I thought of Hitchcock’s Rear Window, and I picked up a copy and read the first sentence:

Her husband’s almost home. He’ll catch her this time.

Have I mentioned I am a sucker for a good first sentence, too?

© 2018 Robert Fairhead

N.B. This post originally appeared on Tall And True. You might also be interested in this blog post on my love of book covers and first sentences, Celebrating 200 Instagram Posts (November 2018).

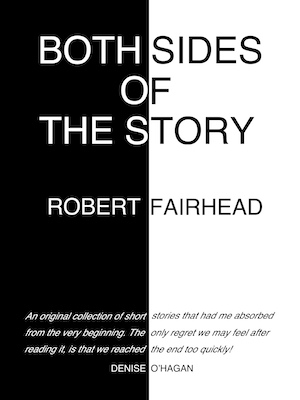

About RobertFairhead.com

Welcome to the blog posts and selected writing of Robert Fairhead. A writer and editor at the Tall And True writers' website, Robert also writes and narrates episodes for the Tall And True Short Reads podcast. In addition, his book reviews and other writing have appeared in print and online media, and he's published several collections of short stories. Please see Robert's profile for further details.

0 Comments