My wife and I visited Turkey in 1988. We had endured our first English winter and spent two weeks hugging the coastal sites and sunny beaches. We returned in 1990, venturing far from the coast to the mountains of eastern Turkey, where Kurds befriended us, and we learned a little of Kurdish culture.

Travelling by bus and dolmus, we had pushed further and further east until we reached the point of no return. At least, not by bus back to Istanbul in time to fly home to England. So we improvised and booked a flight to Istanbul from eastern Turkey instead.

Golden Days of Independent Travel

Those were the golden days of independent travel. When we could improvise and travel in relative safety. Even if it meant we were the only tourists on a crowded dolmus, on a steep, windy road, deep in the Kurdish mountains.

Our relative safety was thanks to the hospitality of the people we encountered on buses and dolmuses. And in towns like Doğubayazıt and Diyarbakir. My travel-journal records many interactions and acts of kindness:

After travelling all day along the Soviet border, we arrived in Doğubayazıt at 6 PM — too late to push on to Van. A tourist rep invited our little group to his office to discuss hotels and excursions. He gave us a good rundown on prices and an itinerary to visit local sites and the Iranian border, before taking us on to Van. After business, he served çay and showed me how to play a tune on his saz. He also gave me tips on tapes to look for in the markets. “Kurdish music,” he explained, “because I am a Kurd, not a Turk.”

We regrouped in the morning and set off in a mini-bus with our guide and driver. The tour included visits to mountain top villages, the impressive ruins of the Ishak Pasha Palace, the “resting place of Noah’s Ark“, and the “world’s second-largest meteorite crater“. With a çay-break at the Iranian border.

A Tourist with a Camera

I felt like an intruder walking through the Kurdish villages, but our guide ushered us on, and the villagers seemed relaxed with our presence. Women laughed at our tourist attempts to help them grind maize with large wooden sledgehammers.

I was also uncomfortable using my camera in the villages — but that didn’t stop me:

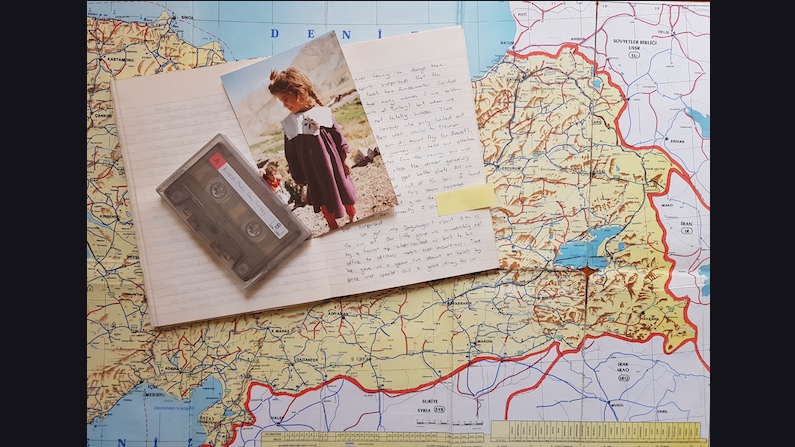

A group of children ran towards us, hands outstretched, chanting, “Bonbons, bonbons.” I took a photo of one young girl and immediately felt guilty because I didn’t have any sweets for her.

Between stops, I chatted with our tour guide. Like the Doğubayazıt tourist rep, he was “Kurd, first and foremost”. On the prospect of war between America and Iraq, he explained, “Saddam is not Kurd, he is Arab, he is fascist.” Yet the guide wanted war, not to defeat Saddam Hussein but to draw Turkey into the conflict. And then, he asserted, the Kurds would take advantage of the situation.

Leaving the Mountains

After the mountains and sparse villages, the sprawling city of Van was a shock. We spent one noisy, restless night there before boarding a morning ferry for the four-hour Lake Van crossing to Tatvan.

The Turkish military presence in Tatvan was significant, with fenced-off compounds and tanks. We didn’t hang about long, catching the first available bus to Diyarbakir.

It was dark when the bus reached the city’s outskirts, which loomed large and bright, a mass of lights. We hopped onto a dolmus and headed into the town centre hoping to find a hotel:

Befriended by a young guy who said he’s home on holidays from studying political science in Istanbul. He took us to a decent looking hotel near the bazaar. On the way, he talked about the futility of a Kurd studying political science in Turkey. And he fended off a couple of cheeky kids who tried to pick my pockets.

A New Friend in Town

The next day, we learned, was a public holiday. The banks were closed, and the “big hotels” in our vicinity would only change money for their guests. With insufficient Turkish lira, we faced a day of bread and water. And then we met another local guy who spoke German. I explained our plight to him in my schoolboy Deutsch, and he offered to change a few of our pounds into life-saving lira.

Afterwards, he invited us to his uncle’s shop near the bazaar for çay. It seemed churlish to refuse the invitation, so we followed him to the shop. But I politely declined, “Nein dankeschön” when the uncle rolled out carpets with the çay. Undaunted, our new friend offered to show us the city walls, and again we accepted:

We climbed the city wall near the remains of a gate — there were no other tourists in sight. From the top, we could see the stark contrast between the fertile strip of the River Tigris, and the dry, dusty plains and mountains in the distance. And behind us, the built-up hustle and bustle of Diyarbakir.

After the tour, our friend led us back to the bazaar to a stall selling traditional baggy trousers. He seemed disappointed I didn’t want to buy a pair. However, he was pleased when he found me a tape of Kurdish music, and I bought it.

We parted with our friend, returning to the hotel to pack for the flight to Istanbul. But as promised, we visited his uncle’s shop to say goodbye before we headed to the airport:

When we arrived at the shop, we found our friend having çay with the young guy who had befriended and helped us with the hotel last night. Neither seemed perturbed by the “coincidence”. Our (newer) friend tried to get us a taksi on the phone, but reported they were all too expensive. Instead, he offered to run us to the airport in his car, for “only 15,000 lira”. What else could we say, but “dankeschön”?

Turkish-Kurdish Conflict

Three years after our trip to Turkey, Kurdish separatists, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), took hostage a British and Australian couple on a cycling tour near Tatvan. They held the couple for five weeks before releasing them unharmed, along with four French tourists (Independent UK, August 1993).

Around the same time, the PKK ambushed and killed thirty-three Turkish military recruits and five civilians. In retaliation, the Turkish military launched a counter-insurgency campaign against the PKK and their supporters, destroying over 3000 Kurdish villages.

Unsurprisingly, the UK Foreign Office advised tourists to avoid eastern Turkey. And the golden days of independent travel in the region were over.

Kurds in the News

Thirty years on, I still have our travel-worn map of Turkey, my journal, the tape of Kurdish music, and the photo of the young girl in the village. She looks about five and would be in her mid-thirties now.

Whenever Kurds make the news — in Turkey, Iraq, Iran or Syria — I think about that girl in the photo. Did her village survive the counter-insurgency campaign? Is she grinding maize with the other women? Do her children beg for “bonbons”? Or does she have another life in a city or refugee camp?

There is a saying, Kurds have no friends but the mountains. In my journal entries, I referred to the Kurds we met and who helped us on our travels as “friends”.

I’m not naive. I know our friendly Kurdish tourist reps and city guides got backsheesh for their services. But looking back, I also believe their presence kept us safe.

I wish the world would do the same for our Kurd friends in the mountains today.

© 2019 Robert Fairhead

N.B. You might also like another blog post from my travel journals on my Three Visits to Dahab, Egypt, between 1991 and 1995.

About RobertFairhead.com

Welcome to the blog posts and selected writing of Robert Fairhead. A writer and editor at the Tall And True writers' website, Robert also writes and narrates episodes for the Tall And True Short Reads podcast. In addition, his book reviews and other writing have appeared in print and online media, and he's published several collections of short stories. Please see Robert's profile for further details.

0 Comments