NAIDOC Week is a celebration of Indigenous Australian culture and survival and usually takes place in July. Being an unusual year, NAIDOC Week 2020 was postponed to November. But it remained an opportunity for Australians to acknowledge our Indigenous people, and to reflect upon a sad and shameful history.

Please note: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are warned this blog post contains the names and images of people who have passed away. “Aboriginal” and “Indigenous” are used synonymously for Australia’s First Peoples. I wrote the post on the land of the Eora Nation.

As I wrote in Alice Nannup and my Nan (July 2020) and The Songlines (Tall And True, December 2017) and, I grew up in Perth, Western Australia (WA), in the 1970s. In those less enlightened days, Australian schools taught very little about the Indigenous inhabitants, or “Aborigines”, as we called them.

We learned they had been in Australia for 20,000 years (now revised to over 60,000 years!) and were nomadic. When “Aborigines” weren’t on walkabout, they sat under trees in parks and got drunk. A few became famous footballers and boxers, and Evonne Goolagong Cawley won Wimbledon. But none were ever my neighbours.

The Real History of Aboriginal Australia

It wasn’t until I left Australia and was living in England in 1988 that I discovered my country’s dark past. Back home, White Australia was celebrating the Bicentenary of the arrival of the First Fleet. Meanwhile, Indigenous Australians and their supporters were protesting against Invasion Day.

In England, the BBC aired news of the protests and documentaries showing the good, the bad, and the downright ugly parts of Australian history. And it made for uncomfortable viewing and pub conversations with English friends for this boy from Oz.

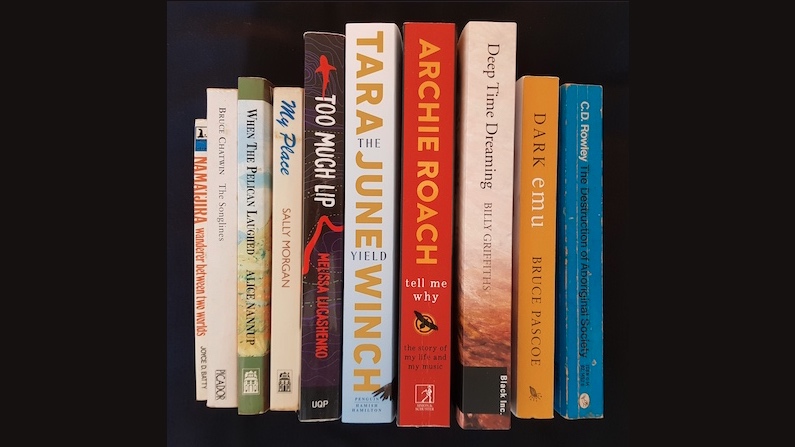

To gain insight into the issues raised on the BBC, I read books by Indigenous and non-Indigenous writers. And three proved seminal in my awakening to the real history of Aboriginal Australia.

The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin

It may seem odd (and perhaps inappropriate) that an English writer, Bruce Chatwin, introduced me to a foundation of Indigenous Australian culture.

But until I read Chatwin’s 1987 book, The Songlines (Amazon link), I hadn’t realised the diversity of Aboriginal nations and languages on the continent. Let alone the existence and significance of Songlines.

Chatwin explained Songlines are more than “maps” to Aboriginal people. They are Dreaming-tracks and a means of bringing the Dreaming into existence. Sacred and ceremonial sites. Title deeds to traditional lands, trade routes and ways of communication.

And Songlines can stretch vast distances and language barriers. As Chatwin wrote:

“A Dreaming-track might start in the north-west, near Broome; thread its way through twenty languages or more; and go on to hit the sea [in the south] near Adelaide.”

As a schoolboy, I may have known “Aborigines” spoke a few different dialects. But not that there are twenty or more languages between Broome and Adelaide. Nor that their Songlines stretch across the continent.

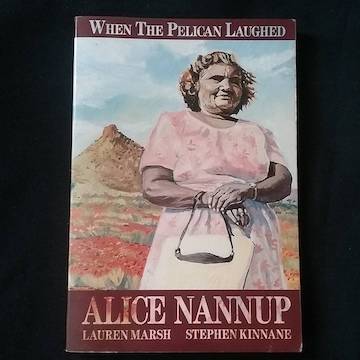

When The Pelican Laughed by Alice Nannup

I bought Alice Nannup’s memoir on a trip back to Australia in 1992. It was the first book I read with a personal account of the Stolen Generations.

As a young, white male, I’d led an insular life in the most isolated city on the world’s largest island continent. Travel broadened my outlook. And reading When The Pelican Laughed (Goodreads review) opened my eyes to the long term systemic racism in Australia.

Alice was taken from her community in the north of WA in 1923 when she was twelve. She was sent south to the Moore River Native Settlement for “education”, a euphemism for harsh training as a servant.

Alice overcame many hardships but never again saw her mother or aunties.

On a personal note, I uncovered a connection between Alice Nannup and my Nan. From 1927 to 1928, Alice worked as a domestic servant for Robert Larsen, the officer-in-charge of the Williams Police Station, 160 kms south of Perth.

From tales my Nan had told me as a boy, I knew that her father had been an officer-in-charge at Williams. So I wrote to her from England with questions from Alice’s book. My Nan wrote back in September 1992, and I still have the letter. In it, she confirmed her father had taken over the police station from Robert Larson.

Could my Nan have met Alice during the handover of the police station? Unlikely. But this “connection” is another reason why Alice’s memoir remains one of my treasured books.

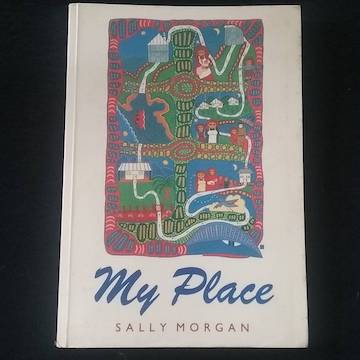

My Place by Sally Morgan

By the time I read My Place (Amazon link) in the mid-1990s, I had no excuse for ignorance about the state-sanctioned separation of Indigenous children from their families and community.

However, the full extent and evil of these policies were not accepted by the majority of White Australia until the Bringing Them Home report was released in 1997.

And even then, it wasn’t until 2008 that an Australian government offered an overdue apology to the Stolen Generations.

Like me, Sally Morgan grew up in Perth, living with her mum, Nan and siblings. Her family’s story is typical of lighter-skinned Aboriginal people in the 1950s and 60s. And Sally’s Nan and mum denied their Indigenous heritage, instead claiming the family was of Indian-Bangladeshi descent.

Sally was fifteen when she learned her Nan was a “half-caste” Aboriginal. My Place is the tale of Sally and her family finding their place in Australia as Indigenous people. It didn’t happen overnight. Sally was married with three children when she published her book. It took many years for her Nan and mum to open up about their Aboriginal background.

And her Nan, in particular, remained wary of making the story public and of government authorities. Sally wrote:

I was often puzzled by the way Mum and Nan approached anyone in authority, it was if they were frightened. I knew that couldn’t be the reason, why on earth would anyone be frightened of the government.

Reading the chapters on Sally’s Nan and mum and how the authorities separated them from their family and communities explains that fear.

Indigenous Fiction and Nonfiction

It’s thirty-two years since the “First Fleet Bicentenary” and twenty-five since I returned to Australia. I’m now a middle-aged, white male, living a less insular life on the opposite side of the continent from my boyhood hometown.

I continue to read books, fiction and nonfiction, to learn more about Aboriginal Australia. My travels may be over, but I’m still on a long journey of understanding.

The Songlines, When The Pelican Laughed, and My Place set me on that journey and provided me with signposts. And reflecting on NAIDOC Week this year, I’m forever grateful for their insight.

© 2020 Robert Fairhead

N.B. You might also like to read a memoir piece I shared on Tall And True about A Perth Boy’s Perspective on the Vietnam War (April 2018).

Note: This post originally appeared on the Tall And True writers’ website.

About RobertFairhead.com

Welcome to the blog posts and selected writing of Robert Fairhead. A writer and editor at the Tall And True writers' website, Robert also writes and narrates episodes for the Tall And True Short Reads podcast. In addition, his book reviews and other writing have appeared in print and online media, and he's published several collections of short stories. Please see Robert's profile for further details.

0 Comments